IntroductionI was a little girl, growing up in Chengdu, the capital of China’s Sichuan region. My parents and I would eat at fly restaurants—tiny, dingy, hole-in-the-wall places that are so good they’re said to attract people like flies. At these popular spots, we’d grab bowls of Sichuan’s best street food and homestyle cooking. The options were limitless: mung bean noodles, slippery wontons, and stewed pork belly topped with brown sugar. These places were nothing to look at, but the energy was unlike any. It was magical. And the flavors? Delicious, layered, and complex.

I didn’t know it then, but those moments sitting crouched on a tiny plastic stool, eating bowls of hot noodles submerged in sweet chili oil were the most transformative of my life.

When I grew up and moved away from Chengdu, the food and memories from those fly restaurants stayed with me. My family relocated a lot—we lived in Germany, England, Austria, France, and Italy. My father was a nuclear physics professor with a Chinese visa, which meant he usually couldn’t teach at one university for more than a year. Throughout grade school, I was always the new kid. I learned to adapt to my environment at a young age and adopted a Western name—Jenny—to try to appear less foreign, to blend in. Transience became the norm, and each year I had to learn a new culture and a new language—until finally, we settled in Canada for my high school years.

During all these moves, food brought me home. My mom would do her best to recreate memories of our favorite flavors, using ingredients she would find at the local European farmers’ markets. They tasted of neither here nor there but were delicious nonetheless. We would occasionally go back to visit our family in Chengdu and return to the fly restaurants. There was something about the buzz of warmth from the sweet chili oil that reminded me of who I was.

I graduated from business school in Canada and went off into the corporate world. Around 2010, a job with a large tech company brought me back to Asia, where I lived in Beijing, Singapore, and Shanghai. It was exciting and intense, but I started to become undone. Who was I? Where was I from? What is my base? You could say I was having an identity crisis of sorts. The transience had caught up with me, and I had no firm ground to stand on.

Being in China forced me to realize how divorced I’d become from my roots all those years and how much I had pushed down and buried them, just to be seen, just to survive. I slowly peeled back the layers, and food gave me the courage to do so. In Beijing, I dug into the rich food culture of the capital, eating at the restaurants of provincial government offices known for most faithfully representing each region’s cuisine. I studied with chefs and food historians and inquired about dishes. And to dive even deeper, I cooked.

It shocked me how wide and rich this 5,000-year-old culinary heritage actually was and how little of it was and is known outside the country. I saw how people came alive over food and witnessed the vibrant complexity of flavors from across the land. A perfect bowl of mapo tofu evoked tears. Chengdu’s Zhong dumplings elicited smiles as wide as the entire country. A deceptively simple plate of pickles tasted anything but. There was life found in these layers of flavors, and more importantly, I uncovered layers of myself in between these bites.

I began to develop my own personal iterations of these complex Chinese flavors. I went on sourcing trips across the Sichuan countryside, learning the specificity of provenance and its impact on flavor and quality. Sichuan is known as the land of plenty, and for good reason. The climate and topography provide conditions for ingredients unmatched, creating flavors unparalleled. I created dishes that married flavors new and old. Everything was an evolution while being rooted in tradition—and I was finding my voice.

I started a popular blog on Chinese food and took celebrity chefs around the country to eat. Eventually, I found the courage to leave my day job and founded an awardwinning fast-casual restaurant in Shanghai called Baoism. Whenever I could, I began hosting “underground” pop-up dinners around the world. I named these dinners, which I held everywhere from Hong Kong to Sydney to New York, Fly By Jing, a name pulled from my roots: an ode to the fly restaurants.

I loved how the layers of flavors in my dishes made me feel and how they made others light up. I often traveled to cook in places where people had never heard of these ingredients or tasted these flavors. Their reactions convinced me that appreciation for great flavor was universal, and there was a gap to be filled.

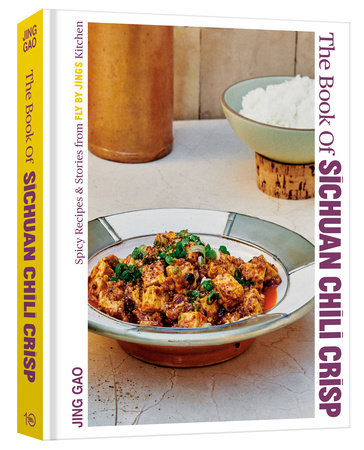

Everywhere I traveled, I kept with me a suitcase of meticulously sourced ingredients. I knew they were key to the flavors I cooked and could not be found anywhere else. I made big batches of sauces, spice mixes, and condiments of all kinds. Chili crisp, the versatile, spicy, umami-rich sauce was a base layer for many recipes as something to build up flavor, and it was something I took for granted. It was a pantry staple in Sichuan, and there were thousands of variations across China, much like soy sauce and sesame oil. Recipes for chili crisp varied from family to family, passed down over generations. I began to concoct a personal blend, honoring my family’s rendition while adding my own nuances. Guests at my dinners inquired about it, and I started bottling the stuff to give to friends and family. Demand grew, and I began selling it online and in local boutiques.

In 2018, I traveled to California to visit a natural food trade show called Expo West. Swimming through a sea of people over several days at the largest food exhibition in the country, I was struck by the lack of diversity in options. I could count on one hand the number of Asian food brands represented, and that didn’t seem right, given how popular I knew these flavors were. I realized quickly that this was my opportunity. I launched Fly By Jing, my line of pantry staples featuring Sichuan chili crisp at its front and center, shortly thereafter via a crowdfunding campaign, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Today, everything I do revolves around flavor. It colors how I see the world and evokes memories and dreams of the future. The base of this flavor was and remains chili crisp. It punctuates my brand and all that I do. But chili crisp is also an invitation to feel and remember and be seen. The journey of building my company has helped me come home to myself. Along the way, I reclaimed my birth name, 婧 Jing.

This book is about this reclaiming. It tells the story of how I found—and continue to find—my identity through food. I am here because I have the utmost honor of being able to cook and explore the food of my home country. Sichuan chili crisp is the vessel through which I’ve been able to express my love for my culture. Fly By Jing’s slogan “Not Traditional But Personal” speaks to the deeply meaningful pillars of heritage and the steadfast honoring of self, both of which is what I founded my brand on.

These pages also tell of the nuanced, layered, complicated, historical, and modern aspects of Chinese cuisines and the unparalleled magic of chili crisp. I say “magic” because it truly is just that. It can take any dish to the next level—from a traditional bowl of dan dan noodles (page 171) to your mother’s favorite lemon cake. Chili crisp is meant to make you get in the kitchen and explore and experiment unfettered. It’s meant to bring you closer to you.

My goal has always been to evolve culture through flavor. I want you to feel seen and heard when you cook and eat, just as I have done. Get curious. Get weird. Get bold.

Throughout all these years, the one truth I’ve learned and kept close is that flavor is a vehicle to tell our stories. When we’re exposed to new sensations on our taste buds, we break barriers in ourselves and with others. That really is magic.

And so is sweet, fiery chili crisp dripping down your lips.

Copyright © 2023 by Jing Gao. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.