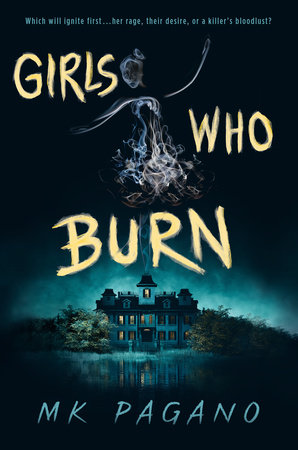

1

The last time I saw my sister alive, I told her I didn’t love her anymore.

I didn’t say it in those exact words. I didn’t say, “Fiona—I don’t love you anymore.” What I actually said, as she was walking away from me, was “You’re no better than Mom.”

But in our family, that means the same thing.

I’m thinking about that again, the parade a blur in the background, Fiona’s blond hair flying around her shoulders as she spun off and headed toward the woods. To the ravine.

In my mind, I go after her. I tell her I’m sorry. I bring her home safely. I don’t wander off to drink my problems away with Seth Montgomery on the star-watching rock. Don’t wake up with Seth’s arms around me and the stale taste of cider on my tongue. Don’t stumble home in the early morning to collapse into bed, only to be woken up a few hours later by the police letting me know my world would never be the same.

In my mind, I’m always a better person than I actually am.

A whistle sounds, startling me back to the present. I’m at the edge of the park with my bike, in the shade of a maple tree, waiting for my brother to finish soccer camp. On the far side, next to the woods, a group of teenage boys disperses from the field. Davy is easy to spot: taller than most of them, skinny, blond hair sticking straight up at the back of his head. He shot up this past year, so he can actually pass for sixteen now, even though he still has that round baby face.

I wave to get Davy’s attention. When he sees me, he jogs over, frowning slightly.

“You didn’t have to pick me up,” he says. “I can ride my bike home on my own.”

“I don’t mind. Besides, Dad’s working late again. He asked me to pick up pizza. Come with?”

He’s about to respond when his head whips to the side. I turn to see a girl on a bike riding into view—a white girl with brown hair.

“It’s not Marion,” I tell Davy for what feels like the hundredth time. I try to sound patient; he’s not the only one seeing last summer’s ghosts. “They’re not coming back.”

Davy doesn’t answer me, just looks pissed, the way he always does when his ex-girlfriend gets brought up. He hops on his own bike and takes off.

We pedal down a few residential streets, and soon we’re on the outskirts of downtown. Bier’s End, in the northwest corner of New Jersey, was once a retreat for wealthy Manhattanites, with lavish mansions on huge pieces of property spread out along the edge of the woods. Now most of those mansions have been knocked down, their giant plots of land divided up, turned into the stretches of middle-class blocks like the one my family lives on. Pieces of downtown remain from that bygone era: the old theater with its velvet seats that plays vintage movies, the one nice restaurant that used to be a country club. But those are now interspersed with the deli, the dollar store, Fiona’s old dance studio. Middle-class things for middle-class people. The pizza place is next to a Wawa.

I stop my bike just outside the pizza place’s big window, behind Davy. My throat tightens as I peer through the glass, trying to make out who might be in there.

“I’ll get it,” Davy says.

I clutch the gold ballerina necklace at my throat, the only piece of jewelry I wear. “Thanks.”

He leans his bike against the wall and disappears through the glass doors.

I stay there in the shade of the building. The hair under my helmet feels sweaty, so after making sure no one’s looking at me, I take it off. I drum my fingers against my handlebars, recite prime numbers in my head.

Two, three, five, seven.

Davy walks out, pizza box in his arms.

And then he stops and stares at something over my shoulder.

I turn, expecting another Marion look-alike.

But what I see makes my heart stop.

Parked five spots away is a black BMW X3. License plate BONES05.

Seth Montgomery’s car.

They’re back.

The Montgomerys live in the city during the year, but they’ve been spending their summers in Bier’s End for as long as I can remember, all of them up at their grandmother’s big old mansion on the dead-end street that gives the town its name. But when June rolled into July and there was no sign of them, I thought they were actually skipping this summer. Not that they’ve ever done that before. But then, I’ve never accused any of them of murdering my sister before, either.

The sweat on the back of my neck has turned cold, and at the same time, I’m mad at myself. I should have been able to feel it. There should have been a ripple in the air, a thunderstorm,

something to warn me. So I could prepare.

Seth isn’t even the one I want to talk to. In fact, he’s the

last Montgomery I want to talk to. But if he’s here, it means they all are.

I can’t see Seth right now. “Let’s get out of here.” I swing a leg over my bike—just as the door to the Wawa opens.

And there he is.

Tall, broad-shouldered, shock of black curls. Stubble thicker than I’ve ever seen it. White collared shirt with little blue stripes, untucked. Khaki shorts. Loafers, no socks.

Seth Montgomery.

My heart flips over in my chest.

Seth looks shocked. I don’t know why;

we’re the ones who live here all year. But then he pulls himself together.

“Addie.” He says my name like an accusation.

I swallow. “Seth.” I say his name the same way, put my foot on my pedal, ready to ride off, even though my helmet’s not on and Davy hasn’t strapped the pizza to his bike. “If you’ll excuse us—”

“I need to talk to you.”

I steel myself. “I don’t have anything to say to you.”

His brows come together. “Well, I have shit to say to you.”

“That’s too bad. Now, can you please—”

“Addie—” Seth’s eyes dart up and down the sidewalk, but the only person within earshot is Davy, staring at us wide-eyed. Seth drops his voice. “Can we talk? It’s important.”

“Is Marion here?” Davy blurts out then. Marion is Seth’s cousin.

Seth turns briefly. “Yeah. She’s at the house.”

Davy’s head whips around, even though their house is miles from here.

“What about Thatcher?” I ask. Marion’s brother, another of Seth’s cousins. The one Montgomery I

do want to talk to.

Seth holds my gaze for a long moment before answering. “We’re all here. Our grandma passed away.”

I’m temporarily speechless. I haven’t seen Mrs. Montgomery in forever. All our time running around in their backyard, we barely went inside the mansion, and in the past few years, Mrs. Montgomery stopped coming outside altogether. I should feel sad; that’s how you’re supposed to feel when people die. But I never knew her all that well.

And my mind is more caught on the fact that Thatcher Montgomery is here, on Bier’s End, for the first time since last summer.

I need to think this through carefully. I can’t just hop on my bike, pedal up to the Montgomerys’ front door, demand to see Thatcher, and ask him, face-to-face, if he pushed Fiona.

But I

do need him to see me. Maybe after a whole year of stewing in his guilt, it’s eating away at him. Maybe all he needs is someone to come along and drag a confession out of him. I could bring my phone, secretly record him, take it to the cops—they’d have to listen to me then, wouldn’t they?

Straight-up confronting the boy I suspect killed my sister isn’t the smartest plan, I know. But I’ve exhausted every other option. I told the police what I thought. Over and over. And they didn’t do a thing about it. Thatcher went back to school in England, his family name and his money protecting him. No one was ever arrested. They called Fiona’s death an accident. That, or suicide.

No one would listen to me, no matter how loud I was.

“I’m sorry about your grandma,” I say to Seth. “But you and I have nothing to talk about.” I jerk my head at Davy. “Strap the pizza on and let’s go.”

But Davy doesn’t budge. “Is Marion okay?”

“It’s been a hard year for everyone.” Seth looks at me again.

“Davy. We need to

go.”

I don’t like the look on Davy’s face—like he’s already calculating how he’s going to run into Marion—but thankfully, he does as I say.

I’m half-afraid Seth will try to physically stop me from riding away. Block my path, demand to know why I never returned any of his texts or DMs. But he doesn’t move. Just watches as I fasten my helmet, despite my shaking hands, and start down the sidewalk—nearly toppling over as I do.

On the ride home, Davy and I don’t speak. We glide past small suburban houses and maples with their leaves drooping in the heat. To the west, the sun is sinking into the tree line. Somewhere, someone is mowing a lawn, the steady buzz of it like the drone of an insect.

I barely see any of it. All I can see is Seth’s face, that expression: surprise, anger, determination.

Desperation.

I need to talk to you.

On Bier’s End there are summers when nothing happens, and summers when everything does.

I touch the gold ballerina at my throat.

When we were little, Fiona and I lived for summer. Running through the tangle of woods that separates our house from the Montgomerys’, meeting the Montgomerys for the first time.

Thatcher was two years older than Fiona; his sister Kendall and their cousin, Seth, were both Fiona’s age. When Davy and Marion got old enough, they’d tag along, too. And summers became synonymous with the Montgomerys: manhunt in the woods between our houses, cannonballing into their giant pool. Daring one another to hop the old stone wall to the abandoned Bier mansion next door and screaming when the ivy brushed our ankles.

Searching for treasure. Legend has it the last Bier took what was left of the family fortune and buried it somewhere on their acres of land.

Sometimes, in my wilder moments, I think maybe that was what Fiona was doing on the Bier property the night she died. Searching for buried treasure.

Because I can’t come up with any other explanation.

She must have been drunk, some people said, wandered off from the Founders’ Day parade and fallen down the ravine. But Fiona didn’t drink.

She must have been meeting up with a boyfriend, others said, and something went wrong between them. But Fiona didn’t date.

She must have done it on purpose, more people whispered. But Fiona wasn’t suicidal. She was leaving for the American Ballet Academy in a week. Her life’s greatest dream realized.

It was an accident, the police finally said. She must have tripped and fallen. But Fiona wasn’t clumsy.

I didn’t believe the police’s verdict. I’m not sure how many other people did, either. Someone saw Fiona and me arguing at the parade. Details from the investigation surfaced somehow: The only sign of another person near her that night was a strand of my hair on her tank top. Her journal had gone missing.

None of that proves anything, of course. My hair could have gotten there anytime. And I don’t know what happened to her journal. I didn’t take it.

It took me a little while to see past the murmurs of

I’m so sorry for your loss, the Cs on tests I should have failed. But the more time went on, the more things shifted. Once I told Jeremy what Seth and I were doing the night Fiona died and he broke up with me for good, I stopped talking to everyone except my own family. People started avoiding me, looking away when they saw me coming. Without Fiona, without Jeremy, without any of the Montgomerys here anymore—it was like the membrane that had protected me was gone. I became a hermit crab, coating myself in hardness.

That’s who I am now. Who I need to be.

What I

don’t need is to hear whatever Seth Montgomery has to say about last summer. About that night or the morning after. I don’t need the drama, I don’t need his questions, and I definitely don’t need him looking at me in that way he does.

It’s only been a year since Fiona’s death. Too soon for anything more to happen. Far too soon.

Copyright © 2024 by MK Pagano. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.