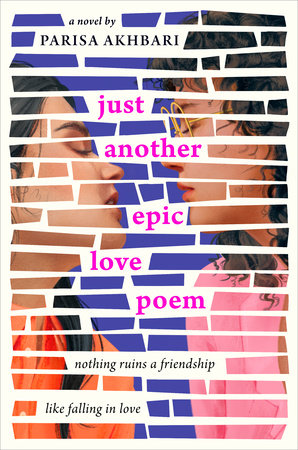

The Never-Ending PoemWhenever she got nostalgic, Bea would ask me, “Do you remember how it started?”

And I wouldn’t need to ask her

What? because I already knew what she was talking about. But she’d coax me on anyway: “The first thing I ever wrote to you.”

I remember how the poem started, I want to tell Bea now.

I remember, I remember. But I think she’d rather we both forgot.

The BeginningBea and I were thirteen when we met, when I transferred into her eighth-grade classroom at Holy Trinity. Bea would fight me on this part, but our friendship—and everything after—began with her pelting me in the back of the head with a wad of paper.

Not that I was a stranger to fielding other people’s spitwads. But my first day had already been off to a miserable start, mainly because of the uniform jumper. It hung in this thick, carpet-like fabric down my body, a pleated headache of red and gold plaid.

This is the first day of the rest of your life, I thought. I looked like a human Christmas tree ornament. And maybe that was the point of Catholic school. How would I know?

We had just moved to Crossroads, the one almost-affordable pocket in the uber-rich city of Bellevue, Washington. I loved our new neighborhood because of its proximity to the Crossroads Shopping Center, home of the only Iranian-owned pizza parlor I had ever heard of. I also loved it because we were surrounded by other brown people. Crossroads felt like a little belly button of familiarity in a giant and strange new city.

But our new school wasn’t in Crossroads. It was in Medina, where everyone had a home tennis court or a pool. And it wasn’t like my old school, which my dad referred to as a “crunchy hippie place” when he found out I spent science class sifting through trash bins to start a composting system. Holy Trinity was a private Catholic school. Which was a weird choice, given that my dad was raised Muslim.

Dad had ushered my eleven-year-old sister, Azar, and me into our new student orientation with a pep talk about how Catholics valued education above all else, and how the teachers would only care that we studied hard. I guess he believed that good grades would shield us—like nobody would notice that we were clearly Iranian American, and didn’t know a thing about Catholicism, because intellect would render us into amorphous orbs of knowledge.

The idea of Catholic school had me convinced I’d be transported into a staging of

The Sound of Music, nuns and all. From the brochures, the entire student body of Holy Trinity looked like a beaming sea of von Trapp children. I half expected them to twirl around in their matching jumpers and suit coats and serenade me with “Do-Re-Mi” on my arrival.

Turns out, didn’t happen.

Dad pulled up to the school grounds that first day, sneak-attack kissing my and Azar’s foreheads. “Make it a good day,” he shouted as we slipped out of the car, his accent snagging the attention of some tall boys in blazers. “Make it the best day of your life!”

That’s how Dad said goodbye to us every day since we left Mom—a charge to make the best of crappy times.

Azar and I headed toward the complex of brick buildings, and she immediately broke away from me, flocking toward a gaggle of sixth-grade girls on the lawn. I kept my eyes on the scattered leaves in front of me, not looking up until I reached the arch at the school’s entrance, which was engraved with the words:

May God Hold You in the Palm of His Hand.

Each building on campus was named after a Jesuit priest or saint, their faces embossed above the doors so that some old, dead white guy was always scowling down at you upon entry.

Xavier—or Creepy Goatee Dude, as I came to think of him—was cavernous, with a long, dark hallway parting two rows of lockers. The space was packed with students huddling by their respective lockers, every single one of them glued to a phone. The front door thudded behind me, and some of the kids looked up, glaring, before going back to sending their last messages before first period. I didn’t even have my own phone; Azar and I shared my dad’s old Galaxy, which meant she was constantly wresting it out of my hands so she could play Pet Rescue Saga or video chat the gazillion friends she left behind in Sacramento. I didn’t need my own phone, because I didn’t have anyone to talk to.

As I worked my way toward the classroom, I snuck glances of the Holy Trinity girls. They all looked so shiny and

wholesome, like they ate apple pie every night and said prayers and flossed their teeth before bed. Some of them had cross necklaces over their jumpers, and they were all wearing knee-high socks, not the crew-cut ones my dad had picked out for me at the sporting goods store. I’d have to ask my dad for a cross necklace so I could go incognito for as long as humanly possible. I wondered how soon it would be before everyone found out that Azar and I weren’t Catholic.

Behind the door of Ms. Byrne’s eighth-grade classroom, thirty-three sets of eyes zeroed in on me. This was the problem with transferring to a new school in October: Everyone had already established a routine, and here I was, shattering their normalcy with my unfamiliar face and my weird crew-cut socks. I tucked into a desk in the corner of the classroom and stared at the crucifix by the doorway. Jesus, blue-eyed and bleeding, hung stretched out on the cross. Beads of red paint circled the nails in his palms and feet. His head lolled to one side under a crown of thorns. It struck me as pretty graphic for a school where you weren’t allowed to expose your collarbones or wear nail polish.

“Jesus was a nice guy,” my dad had told me when I asked him why we were going to Catholic school. Lots of Christians don’t know this, but Jesus was revered as a prophet in Islam, and there is even a whole chapter in the Qur’an named after Mary. But I had never seen a dead body like this before, sculpture or otherwise. It made me rethink the cross necklace idea.

“Peace be with you, class.” A light-skinned woman with smooth brown hair broke my focus. She wore a gold blazer and knee-length skirt with a red-and-gold tie. Going off her outfit alone, I could tell she was nothing like my old teacher Edgar. He smelled like pipe smoke and his jeans were chronically mud-stained from helping us collect earthworms for our compost project. Anytime one of us shoveled up a worm from the garden patch, he’d say something ridiculous like “Ya dig it?”

Ms. Byrne pulled out a clipboard for roll call, and I allowed myself to peek at the other students as their names were read aloud.

Tristan? Leah? Savannah? Matthew? Spencer? All of them wore red jumpers or blazers, and they all whirred together in my brain like one of Azar’s berry smoothie blender experiments.

“Beatrice?”

My eyes wheeled to the row behind me. Beatrice teetered on the back legs of her chair, the metal frame creaking beneath her. She wore round glasses, her knee-highs were mismatched, and her haircut was definitely of the DIY variety. And still, somehow, I knew she was cooler than me. Not

popular, I guessed, but memorable. Other kids looked to her when her name was called.

She met my eyes. “Bea,” she said to Ms. Byrne—and also, it seemed, to me.

“We don’t use nicknames at school, Beatrice,” Ms. Byrne said, returning to her list. “Oh yes, that’s right. We have a new student joining us today.” The teacher scanned the back of the class and landed on me. “Mitra . . .” She stalled. “How do you say this?”

My voice was stuck in my gut somewhere beneath the shir berenj

I’d had for breakfast. “Esfahani.”

Bea was still watching me. Her skin was amber-brown like mine, but with dark freckles dusting her nose.

“Es-fa-

ha-ni.” Ms. Byrne jotted down a pronunciation note on the roll call sheet. She was trying to be helpful but had already spent ten more seconds focused on me than I could handle. “What kind of name is that?”

As she asked, it occurred to me that I should’ve practiced answering these kinds of questions at home. Then I’d be a pro at deflecting any inquiries into my background. Like Wonder Woman, when she used her bracelets to deflect hundreds of whizzing bullets.

But I didn’t have magic Amazonian bracelets, so I winged it. “It’s, um, a last name?”

Bea laughed so hard that it verged on inappropriate.

“Okay,” Ms. Byrne said, mercifully choosing to move on. “Welcome, Mitra.”

She set down her roll call sheet and faced the class. “Today we’re going to continue our unit on poetry. Page one eighty-one, Billy Collins’s ‘Litany.’ ”

Everyone except me pulled out thick textbooks and flipped through the pages. I glanced at the girl next to me, who had red ringlets over her eyes. I could make out some of the poem on the page of her open book, but when she caught me looking, she blocked my sight with her elbow.

“Follow along with me,” Ms. Byrne said.

I dug my thumbnail into the wood of my desk. The poem started like this:

You are the bread and the knife,the crystal goblet and the wine.It continued describing its subject through metaphors like that, bringing images of birds and bakers and bright sunshine clear into my mind. And it named what the subject is

not: not the plums on the counter,

certainly not the pine-scented air.

When she finished the poem, Ms. Byrne lifted her eyebrows at us. “Reactions?”

Bea’s hand shot up.

“Yes, Beatrice.”

“I like the images. I like the ‘burning wheel of the sun.’ But, who does this guy think he is?”

“Pardon?”

“He keeps saying ‘You’re

this, you’re

that, you’re

definitely not that,’ ” she said. “What if I

am the pine-scented air? Where does he get off thinking he can tell me what I am? He doesn’t know my life!”

A boy behind me chuckled.

“All right, Ms. Ortega. Calm down,” Ms. Byrne said, pinching the bridge of her nose. “Time for small group discussions. Pair up with your partners and share your responses to ‘Litany.’ I want you to identify how Billy Collins uses the elements of poetry we’ve been learning about: form, sound, imagery, metaphor.” A teacher’s aide knocked at the door, and Ms. Byrne stepped out of the room.

Everyone turned toward the kid next to them, and I just sat there, not sure who my partner was supposed to be.

“I have to work with the new girl,” the redhead beside me whispered loudly to a girl across the aisle from her.

Her friend groaned. “Don’t work with the

new girl,” she whined. “Work with

me.”

My chin sunk toward my chest, and my eyes locked on the crucifix again. It would be a lot easier to blend in if I at least had a textbook to look through. I kept hearing my dad’s voice in my head:

Jesus was a nice guy.

Then,

flick. Something soft bounced off the back of my head.

Excellent. My first day at Holy Trinity, and my head was already serving as the backboard for someone’s private game of basketball. The kids around me stopped chattering, and I took in a slow breath. Then I twisted around in my seat and found it: a wad of crumpled paper. I kept it closed in my palms and slumped back into my chair.

“Hrrm,” someone coughed. “

Hrrrm!”

It was Bea. When I looked at her, clueless, she rolled her eyes and then made a gesture with her hands, like she was unfurling a scroll.

I stared back at her for a moment too long. Then I opened my hand and smoothed out the paper against the edge of my desk. Tiny purple writing emerged from the inside of the page.

They say you’re just the new girl

but they should know better,

you’re really the jelly

holding the sandwich together,

I’m a thunderclap

not some goblet of wine,

Holy Trinity sucks

but at least my poem rhymed.

—Bea-lly Collins

Ms. Byrne came back, and I hid Bea’s note in a pleat of my jumper. Nobody had ever written me a poem before. Unless you counted the improvised rhymes Azar liked to scream at me whenever she was mad, like

Mitra’s alone sitting in a tree, F-A-R-T-I-N-G! But those were more spoken word performances than actual poems. When I finally worked up the courage to look back at her, Bea tilted her head to one side and lifted an invisible pen in her hand, scrawling imaginary cursive in the air.

She wanted me to write back.

When Ms. Byrne turned to the whiteboard, I inched Bea’s poem out of the pleat in my skirt and scribbled something down. When my moment arrived, I chucked the paper ball back at Bea.

She unfolded it immediately.

You're the thunderclap

and the flash of bright light,

I'm the bunny down below

watching the sight,

I'm sorry to tell you

but I think we're outmanned-

we are both held hostage

in The Palm of God's Hand.

A grin broke across her face, lifting the rims of her glasses.

There was a flicker, even back then—one tiny flash of feeling in the empty shell of my chest. I called it relief.

I didn’t know to call it love.

Senior YearMitra: you’re late

Bea: always

Mitra: you’re not sorry?

Bea: never sorry

Bea: important business

Mitra: mass is mandatory.

Mitra: so is not abandoning your best friend

Mitra: on the first day of our LAST SEMESTER OF SENIOR YEAR

Bea: YOU KNOW HOW I FEEL ABOUT ALL CAPS

Bea: THEY’RE CONTAGIOUS

Mitra: stop

Bea: I CAN’T MITRA, I’VE BEEN INFECTED!!

Mitra: . . .

Bea: THIS IS GOING TO BE A LONG DAY FOR YOU

Mitra: I’m walking into chapel now

Mitra: putting my phone away

Mitra: if you get here before communion I’ll forgive you

Bea: PRAISE TO YOU

MassIt’s the first day back at school after winter break and I’m stuck in chapel packed with the red-and-gold student body of Holy Trinity, with “Alleluia! Sing to Jesus”ringing in my ears. Mass feels nightmarish without Bea, especially after she coaxed me into that Catholic horror movie marathon over winter break. This is not how I wanted to start the last semester: friendless, my eyes whirling between the statue faces of the saints, trying to detect any signs of demonic possession.

“You having flashbacks to

The Devil’s Doorway?” Bea’s voice slinks into my ear from the pew behind me.

“Flashbacks would suggest I actually watched any of it,” I say. “Most of my view was obscured by your crochet blanket.”

“Fair point,” she whispers.

If Bea were a witch, her magic would be coiled up in her voice. She can broadcast it loud and low when she wants to, like when she used to ward off middle school mean girls with just a word. Those growls I could handle. It’s when her voice turns quiet that I get restless: It’s so soft, too close. It sprouts a wave of goose bumps along my neck.

Bea must notice them, because a tiny breath of her laughter hits my skin. “I didn’t mean to traumatize you,” she says.

I’ll let her believe it’s fear that lights the hairs on my neck. “Next time, I pick the movie,” I say. “Something with kittens and rainbows. Fun for the whole family.”

Father Mitchell’s voice scrambles toward the high notes of the hymn, teetering around off-key. “What he lacks in vocal training, he makes up for in sheer conviction,” Bea says solemnly. “But could he sing to Jesus a little softer?”

“Quiet,” I whisper. Bea hates the hymns and psalms and stuff, but I don’t mind them. If I look at them the right way, it’s easy to find poems in them.

PSALM 91He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High will rest in the shadow of the Almighty. I will say of the LORD, “He is my refuge and my fortress, my God, in whom I trust.”

Surely he will save you from the fowler’s snare and from the deadly pestilence. He will cover you with his feathers, and under his wings you will find refuge; his faithfulness will be your shield and rampart.

You will not fear the terror of night, nor the arrow that flies by day, nor the pestilence that stalks in the darkness, nor the plague that destroys at midday. A thousand may fall at your side, ten thousand at your right hand, but it will not come near you. You will only observe with your eyes and see the punishment of the wicked.

If you make the Most High your dwelling—even the LORD, who is my refuge—then no harm will befall you, no disaster will come near your tent. For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways; they will lift you up in their hands, so that you will not strike your foot against a stone.

You will tread upon the lion and the cobra; you will trample the great lion and the serpent. “Because he loves me,” says the LORD, “I will rescue him; I will protect him, for he acknowledges my name. He will call upon me, and I will answer him; I will be with him in trouble, I will deliver him and honor him. With long life will I satisfy him and show him my salvation.”

you

shelter thousands

under the fortress

of your feathers

you

command night

and make refuge,

shield me from

my snared

fear, come delivering

arrows, guard my

name in your hand

Bea slips one of her wireless buds into my ear before I can argue with her about church etiquette. “It’s not auditorily possible for anyone to hear us over that pipe organ,” she says. “I can feel it in my bones.”

Auditorily? I mouth. She must be desperate for escape if she’s resorting to made-up-sounding words. My messy morning hair does a decent job of concealing the earbud, but Bea always insists on blasting music at eardrum-bursting volume, because “if it’s not loud, we’re not

really listening.”

The church is at capacity this morning because this Mass is not optional—in honor of our first day back in school, we get our cells rattled by the death groan of the pipe organ. The chapel is divided by grade, with seniors occupying the last few pews, maybe a nod to the fact that we’re on our way out. Our bodies are here, but our souls are caught in some timeless dimension waiting for our college admission letters.

When I first started at Holy Trinity, my sole mission was to survive long enough to work my way back through these pews. Study hard, stay quiet, and get out. The

getting out part glued Bea and me together from the start. To Bea, Catholic school feels like one prolonged slap on the wrist from her parents. But staying quiet is my own rule. Silence has never been Bea’s style. She starts humming along to the King Princess song blaring in her earbuds, and this kid Jason from French class turns his head to glare at her.

“Do you want to get stuck on bathroom duty again?” I whisper over my shoulder. There are no detentions at Holy Trinity; here, it’s Service Work. Not that I’ve ever been put in Service Work. But Bea’s shenanigans have led her to scrub out more than her share of toilets. Before winter break, she got a week of Service Work for “defacing school property” after she covered the gendered bathroom signs around campus with rainbow duct tape.

“Music is a healthy distraction,” she tells me.

She’s needed a lot of distractions lately.

Across the aisle, Cara Liu thumbs through a hymnal, her black hair blocking her tan face from our view. But that doesn’t stop Bea from looking, because she’s a glutton for self-punishment. Cara was Bea’s first real love and most brutal heartbreak. I watch as all traces of church-mischief glee drain from Bea’s face.

Down the pew from Cara are Max Jasinski and Ellie O’Reilly. Ellie’s head bobs with imminent sleep, and Max jostles her with a free hand, the Bible flopped open in Max’s lap.

We never used to need an aisle to separate us in church. The five of us used to sit together at every mandatory Mass. Ellie and Bea groaned their way through the sermons, Max and Cara sung dutifully along to all the hymns and refrains, and I tried not to sneeze when Father Mitchell waved around his pungent incense. But that was before the breakup.

I rap my fingers on the wooden back rest of my pew, trying to break Bea out of her daze, and she wrenches her head back to me, forcing a smile.

“Just hold on,” I whisper. “As soon as Mass is over, we’re ascending this purgatory.”

“Poetry seminar!” Bea hisses back at me with a smile.

Bea told me about the seminar in eighth grade, and we’ve been holding it out like a carrot in front of each other for four years, a prize that will make all the Holy Trinity nonsense worthwhile. It’s open only to seniors, and the teacher, Ms. Acosta, makes everyone submit a portfolio of writing samples to even be considered. We have our first class right after church. Assuming Bea doesn’t get kicked out of Holy Trinity for blaring gay music during Mass.

When we stand for Communion, she reaches under my hair to take the earbud back, pocketing both of them.

“We’ll be good. If you’d really rather listen to Father Mitchell, I’m not gonna get in your way. You know he’s probably gearing up for ‘Come, Holy Ghost’ next.” She slips into step with me as we march down the aisle in the procession of students, casting one last glance at Cara.

Nobody questions Bea cutting in line. People here act like we’re interchangeable humans, probably because we’re two queer brown girls in this conservative bastion, and the uniform coordination isn’t helping. But her family is from Mexico, not Iran, and she’s the social kind of introvert, whereas I still think “hanging out” over lunch break means simultaneous silent reading time in the empty chapel.

“So.” Bea sneaks her words in between the organ chords. “You don’t want to know why I was late?”

A smile rises across my face immediately, a flashlight beaming down the dark aisle. I already know.

“I brought you something,” Bea says, pulling something from her backpack.

The Book.

The BookNot the Bible, but our book—the thirteenth one in a line of notebooks we’ve been writing back and forth in, ever since that impromptu poetry swap on my first day of eighth grade. One long poem, a never-ending thing. My hands itch to open it. But I won’t allow myself to read it yet. Whenever it’s my turn with The Book, I want to devour Bea’s writing and somehow also savor it, like the too-sweet last bite of cake. Every single one of her poems is a shiny little gift.

Even when they’re laced with heartbreak.

The Rules of the Never-Ending Poem

For our eyes only!!

Each new verse has to start with the line word the last person ended on.

Terminal punctuation is hereby BANNED. No question marks, exclamation points, periods, or anything else that signals an ending-because this is an endless thing.

Say what you gotta say, and don’t tell take it back! No rewriting, no tearing out pages, no apologizing for your writing.

No criticizing each other's writing-or each other. The Book is for building each other up.

Total honesty—because what’s the point of The Book (or our friendship) if we don’t tell each other the truth?

And then one unwritten rule, just for me:

You can be honest about everything, except the one thing that would destroy your friendship. No letting your love for Bea show.

ConfessionLoving Bea isn’t a choice. Love is the reflex to Bea existing at all. Like squinting at the sun, or shivering when she touches the back of my neck. My body just knows to do it. I can’t control a reflex, and that petrifies me.

In the past, Bea was off-limits. She’s always had some kind of romantic possibility in the works. There was Cara, and before Cara there was Harper, and before Harper there was Natalie, whom she sort of dated at the same time as Harper.

Bea attracts romantic entanglements like cat hair to a lint roller. She can’t help it, it’s just how she is. And because she was always taken, I could seal her off behind a brick wall of

Best Friend in my mind. I made watertight boundaries. But now that she’s single, all my feelings are starting to leak through.

If I had to pinpoint a beginning, it’s this: The summer after sophomore year, Bea came over for one of our marathon nights of chatter and reading and snacks, which she’d just started calling wake-overs, because we were terrible at remembering to sleep. Around eleven, Bea pointed out my bedroom window. “Up for stargazing?”

The window formed a perfect portal to a flat section of rooftop; we’d only ever gone out there for daytime sun-soaking. But it was a gorgeous night, and Bea put on her begging eyes.

We dragged blankets, books, and a thermos of chai through the mouth of the window and made a nest on the rooftop. The June air filled my nose with earthy, after-storm smells. Bea in the blanket was soft and cozy, and the night around us sighed with breeze.

The darkness gave me permission to ask Bea the question that had camped in the back of my brain since we were thirteen.

“Why did you single me out that first day?”

I homed in on her face. Bea’s curls expanded in proportion to how late we stayed up. The tip of her nose flushed warm from chai, and her chestnut eyes lit with the glow from my bedroom lamp.

“I could’ve been literally anyone,” I said. “You didn’t know what you were getting into.”

“You looked like a reader.” She shrugged. Like it was so easy for her to choose me. That first choice catalyzed a thousand others, and there we were, still bobbing in the ripple of her paper scrap.

“I thought . . .” Her eyes tracked mine. “I guess I thought we’d understand each other. And we did.” She reached into the blanket tangle and brandished The Book. It was our first one, with a tattered black cover and red-ribbon bookmark. “Thought we could read some together.”

She shed her glasses and brought her face close to our thirteen-year-old handwriting. I expected her to cringe at our dorky rhymes, but instead she smiled this private smile and huddled closer to me in the blankets. I leaned into her side and rested my head on her shoulder while she read, my cheek nuzzled into her collarbone.

Maybe I was the only person who got to see this Bea: the wee-hour Bea, starry and bound up in wonder.

“Look at us,” she said.

When she read the passages to me, her mouth carried everything. All the awkwardness, all the treasures. Her voice wrapped around me.

In that moment, I knew it: I loved Bea. And not in the way I should’ve loved her, if she were only my best friend. This was a whole new layer of feeling, like that night had stripped the haze off everything around me.

And swirled up in the rich darkness of that night, loving her felt possible. Like I’d found some way to stretch beyond friendship and reach something deeper. Like maybe, just maybe, she could love me too.

But then she put The Book down and started analyzing a thirty-second conversation she’d had with the popcorn girl at the Crossroads movie theater who she’d always suspected was gay.

“I think there’s something there,” she said. “You know? Maybe I should go for it.”

And just like that, the possibility burned away.

When we crawled back into my room, evidence of our friendship was everywhere: pictures of us with Azar in our uniforms on the last day of school; ticket stubs from our trip to the Butterfly Exhibit; a tragically ugly teacup we made at Paint the Town. Panic iced up my spine. Bea was everything to me. Without her, I’d have no one.

I couldn’t gamble our friendship on the improbability that it could become something more. Love meant something different to Bea than it did to me: She fell hard and fast for crushes, like tripping face-first on pavement. My feelings were a slow, sinking sort of love. Like easing into a hot bath that leaves you dizzy and slack. If I let myself sink in further, I would never come out again. I couldn’t allow any more space to that unruly feeling. I had to be okay with the fact that Bea didn’t feel the same way about me.

That night, I lay with my arms and legs stiff against me, while Bea flopped around in the bed beside me. Her fingers twitched against my arm when she dreamed.

Everything had changed for me. But nothing had changed for Bea.

After that, I didn’t let myself wish for anything when it came to Bea. Except one thing: I wished I could love her even a little bit less.

Copyright © 2024 by Parisa Akhbari. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.