1.Before the Castle of Chaluz, Near LimogesMy mom kicked me out. My behavior was getting out of control. Plus, she said, a teenage boy needed his father. So I went to live with Dad. He had a little town house. There was no town anywhere. I guess it's a polite term for "little house." The kind of house that would be respectable in the city, where land is expensive, but dropped out in the distant suburb of Libertyville, where land is cheap. Very cheap construction.

We lived in a small subdivision of town houses surrounded by empty land waiting to be developed. No sidewalks. No one knew anyone. No one's face held any kind of future for any neighbor, and so you couldn't even remember what the people who lived right next to you looked like. Always surrounded by unfamiliar faces. Just like in the city. But here there were only maybe twenty of us. In this subdivision. Maybe less. The subdivision was called Chariot Courts. We lived at 12A.

In the winter it was almost completely exposed. The raw death of the endless future, which at night in the Midwest in winter is sometimes bare inches above the roofs. Cheap housing's always more or less exposed. There was a housing project in Chicago where they found a four-year-old girl dead of old age. That was the coroner's conclusion, after examining her organs. It happened in the nineties. The coroner's report was supposed to be secret, but Larry's stepdad was a cop and he saw it. He had pictures of Dahmer's apartment too, pictures the newspapers never got. They shut that housing project down, farmed the residents out into town houses.

Chariot Courts wasn't the worst in terms of low-grade housing-far from it. The builders had wrought a few charms against total exposure to time. The name, first of all. And there was a cast-iron gate. If you could call it that. It was an odd gate, perched on an island in the center of the subdivision's entrance. On the right you had the drive going in, and on the left you had the drive going out. In the center was this little grassy island and in the middle was the gate, supported between two brick pillars. The pillars were maybe four feet high. The gate was maybe three feet wide. Real wrought iron. The bars bent into fantasies and curlicues of iron, and in the center the swirls thickened into letters:

chariot courts

The gate had a handle, but it never opened. I mean, you could walk around to the other side easy enough. But you couldn't go through the gate. Me and Ty tried to open it one time when we were drunk.

"This fucking thing," he panted, pulling on the handle.

"It's closed," I said stupidly.

He stopped pulling, stumbled back. Looked at it.

"It's like they knew they couldn't really close this place."

I knew what he was thinking. Half the time we knew what the other was thinking.

"There's no way to really close a place like this," I said.

"It's so cheap," Ty said. "Squirrels could probably afford it."

"Wind could afford it," I said. "Trash."

"Remember that Styrofoam cup we found in your living room?" Ty said. "And no one knew how it got there?"

"Anything can come in," I said.

"If it wants to," he said.

"But they made sure no one could go through the gate," I said.

"They closed what they could," Ty finished.

The gate was the second charm. The third charm was the mailboxes. They were made out of wrought iron like the gate. There was no place to put your name. I mean, people were moving in and out of Chariot Courts all the time. Some of the unfamiliar faces were actually new, in the sense of not being here yesterday. Most places like that, the mailboxes have a little window where you can stick a scrap of paper or an index card or something with your name on it. But these mailboxes were above that kind of thing. They came from the eternal motionless past. You had to write your featherlight name on a piece of paper and tape it next to the box. Your name written on wind. Your squirrel name. The mailbox itself wouldn't acknowledge the possibility that a resident's name could change.

I was fifteen when Mom kicked me out and I moved into Chariot Courts with Dad. Those three charms meant a lot to me. I associated them with money. When there's nothing solid behind the present moment, when there's no real past, no tradition, when everything's basically exposed to the future, everything's constantly flying away into the hole of the future, money is the next best thing. The gate and the mailboxes and the name were like pieces dropped off of real houses. In a spiritual sense they were the heaviest objects around. They helped to weigh the place down, on nights when the future hung its open mouth above us, and the years burned like paper in our dreams.

It happened in the middle of January, when I was sitting in geometry class. Winter in Illinois, the flesh comes off the bones, what did we need geometry for? We could look at the naked angles of the trees, the circles in the sky at night. At noon we could look at our own faces. All the basic shapes were there, in bone. Bright winter sun turns kids skinless. Skins them. But there we were in geometry class. The teacher also taught physics. He was grotesquely tall. Thin. He'd demonstrate the angles on his bones.

This was Catholic school. The blackboard was useless. A gray swamp dense with half-drowned numbers. Mr. Streeling would bend a leg in midair: ninety degrees, cleaner than a protractor. He'd stand and tilt his impossibly flat torso: forty-five degrees. He could lift his pants leg, unbundle new levels of bone like a spider: fifteen degrees, fifty-five, one hundred . . .

"So this is an acute angle"-he lifts his leg. The girls turn away. The guys stare in mute fascination. Mr. Streeling graded girls' tests on a curve.

I was sitting in geometry class under the fluorescents when it happened. The first time, technically. Though I could only tell it was the first time in retrospect, looking back from the third time. This must have been in early January. My right hand on my desk, my left hand fiddling with a pencil in the air.

Mr. Streeling's voice booms out, "Open the textbook, page ninety-six." The textbook lies next to my hand on the desk. Next to the textbook is a large blue rubber eraser. Hand, textbook, eraser. Desktop bright in the fake light.

My hand, I realize slowly, it's a . . .

thing.

My hand is a thing too. Hand, textbook, eraser. Three things.

Oh.

That's when I forgot how to breathe. Ty saw it happen. He was sitting across the room. The teacher didn't allow us to sit together, no teacher did. But he saw me, and he gave me a look like

what the hell. Watching me trying to remember how to breathe. It wasn't going well. I was sucking in too much air, or I wasn't breathing enough out. The rhythm was all wrong.

Darkness at the edge of vision . . .

Two seconds blotted out . . . when I came back my lungs had picked up the tune. The old in-and-out, the tune you hear all the time. If it ever stops, try to remember it. You can't. Breathe in, breathe out, breathe in, breathe out. It never stops. But if it does, it's hard to remember how it goes. Ask dead people. Ask me. I gave Ty a shaky smile, like I'd been joking, my face probably red or maybe white or even a little blue. Ty turned slowly back to his textbook, shaking his head, like I was crazy. The idea that I was crazy and he was evil was the background joke of our friendship. It didn't bother him to see me like that. He didn't mention it.

The second time, it happened in a movie theater. My dad had taken me to see

The Godfather III. It was a Tuesday night. Late January. The theater was basically deserted. Kind of depressing, this father-son outing on a school night. Kind of cool too. Like we didn't give a fuck about school nights.

I think the show started around ten p.m. Everything was fine. The film was pretty good. Until halfway through when the Al Pacino character gets diabetes. As they said that word,

diabetes, I could feel gas rising in my blood. The gas started to rise maybe a minute before

diabetes. Like I knew they were going to say it. Like I prophesied it.

This time what I forgot was how to move blood through my body. My blood stopped. When your blood stops, the gas rises. That's my experience. Gas rising in the blood. Dad snored beside me. I woke him up, said we have to go. He looked at me. Ok.

As soon as we got up my blood started to move again. I was still in shock or something. Walking like I was about to fall over. When we got to the car I lay back in the passenger seat and pressed my forehead to the cold glass and Dad asked me if I was ok and I said yes, which he knew was a lie, but there was nothing else I could say.

I couldn't tell him that my blood had stopped. I couldn't tell him about the gas in my blood. Those were inside symptoms, not outside symptoms. I knew on some intuitive level that my blood stopping at the word

diabetes wasn't a symptom Dad could work with. There'd be questions. Plus my blood actually stopped about a minute before the word that caused it. Hard to explain.

In fact there was nothing that could be said between myself and Dad about what happened to me in the theater. So it was the same as nothing happening. That was the second time.

The third time occurred two weeks later. A Sunday night in February. I was in my bed. 12A Chariot Courts. Typically my bedtime on school nights was ten thirty. I had to get up at six thirty to eat breakfast and shower. The bus came at seven. Dad went to bed at nine. When he was home. Which wasn't every night. He got up at an absurd, legendary hour. Four a.m., a time that no fifteen-year-old has ever seen. Until then.

On that Sunday night I climbed into my narrow bed in my narrow room at Dad's place. If you want to imagine what's on the walls of my bedroom, you can picture nothing. Just bare white paint. In reality there probably was something on the walls, but I can't see it from the angle I'm looking at it, coming from the future.

It's possible there was nothing on the walls. Divorced guys have a limited range of wall covering options when furnishing a town house for their kid who unexpectedly comes to live with them. One of those options, maybe the only option, is nothing.

I wonder sometimes if there had been something on the wall, whether the third time would have happened. If the third time didn't happen, the first two would have vanished on their own. Then who would I be?

If the wall of my bedroom had a picture of a sailboat, for instance. Or a picture of a castle. What if there had been a piece of wrought iron fixed to the wall? An old, ornate knocker. Maybe a fourth charm would have been enough.

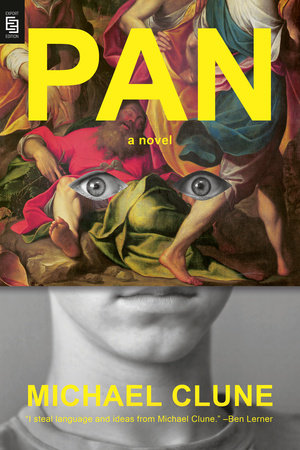

I was reading

Ivanhoe. The old Signet Classics paperback edition. There was a painting of a joust on the cover. A lot of red in the painting, I remember that. But not from bleeding knights like you'd expect. The knights were whole. The red was in the atmosphere. I sat up in my bed with my pillow propped against the wall and opened the book and started to read. It was probably ten fifteen or so. I usually read for a little while before falling asleep.

At a certain point early in the first chapter I became aware that I was having or was about to have a heart attack. As long as I kept reading I didn't have to think about this too much. When you're reading, the words of the book borrow the voice in your head. Words need a voice. The voice they use when you read is your voice. It's the voice your thoughts talk in. So if you give the voice to the book, your thoughts have no voice. They have to wait for the ends of paragraphs. They have to hold their breath until the chapter breaks.

So the lords and the ladies went to the joust, and the Saxon guy threw meat to his dog in his hall, and the other Saxon guy ran away, and the Jewish guy spoke to his daughter, and I was having a heart attack, and the Knight Templar looked down from atop his warhorse. He had an evil gleam in his eye.

I read at a medium pace. Too fast and the voice in your head can't keep up with the words. That's what your thoughts are waiting for. They catch the voice and flood your head with news of the catastrophe unfolding in your body.

But if you read too slow, then it's not just the chapter breaks you have to watch out for. Now you've got holes and gaps between the words. Maybe in some situations that's a good thing. You can savor the words. The words come swaddled with silence, like expensive truffles come swaddled, each one separate, while cheap chocolates are packed next to each other with their sides touching.

In a reading situation like mine you want the words packed next to each other with their sides touching. Because silence isn't delicate truffle-swaddling in that situation. It's heart attack holes. It's not even silence. Every second the book isn't talking, your thoughts are talking, urgently, telling you about this heart attack you're either having or about to have.

So I read at a medium pace. A constant, medium pace. I developed a technique where I'd read over the chapter breaks, and run the paragraphs together. I didn't pause. Sometimes I'd feel myself speeding up-the voice in my head began slipping on words. But I didn't lose it. I slowed down. Not too much. I kept the pace medium.

By chapter three I had it cold. I was a genius at reading Ivanhoe by chapter three. I doubt it's ever been read so well. It had a voice all to itself, with no interruptions, and no breaks, for the entire length of the book. How often has that happened in the history of

Ivanhoe? The whole time I was reading I never even found out whether I was actually having the heart attack or just about to have it. That's how good an

Ivanhoe-reader I got to be. The very next thought would have told me. But the next thought never came.

Copyright © 2025 by Michael Clune. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.