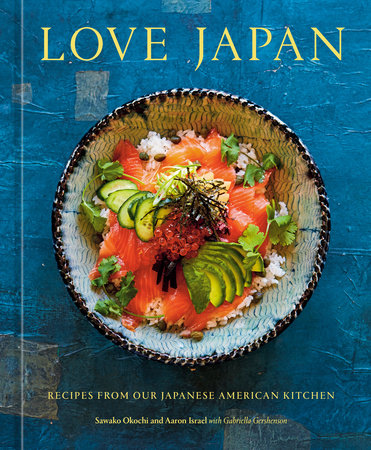

Gohan Desuyo! (Time to Eat!)At its core, this cookbook is a love story about how two chefs from different worlds fell for each other, and for each other’s cuisines. We met in 2011 in New York City on a setup at a Chinese restaurant, which was soon followed by a procession of late-night dinners out, leisurely home-cooked breakfasts, and rooftop beers during the odd hours that chefs keep. Eventually we fell in love, moved in together, and decided to go all in and open our own restaurant, Shalom Japan, in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. It’s a quirky, improbable project, a Japanese-Jewish restaurant that melds the foods of our roots, which for one of us is in Hiroshima, Japan, and for the other in a Jewish American household on Long Island. To some, the concept may seem like a novelty, but for us, it’s a reflection of the life we built together, one in which matzoh ball ramen and lox rice bowls are as commonplace as spaghetti and meatballs are in other families.

As important as the restaurant is to our lives and livelihood, this book isn’t about that. It’s about the food that we cook and eat in our Japanese American kitchen. When we started to build our life together, it became clear how much we were influenced by Sawa’s mother’s home cooking, which is as flavorful as it is nutritious, heavy on vegetables and fermented foods, with lots and lots of variety. (She’d always tell Sawa to eat thirty ingredients a day so she could get nutrition from varied sources.) We wanted to provide the same nourishment for our family, and to yours. Whether or not you have a Japanese parent (or in-law), we still want you to be able to experience the unique pleasure of digging into a heaping platter of golden karaage (fried chicken) or crispy, juicy harumaki (Japanese spring rolls).

Love Japan is our way of sharing these meals that we cherish the most with you.

Our life together hasn’t been a straight path. Balancing restaurant life and family life hasn’t been easy. Along the way, we’ve faced enough challenges to fill a whole other book, and, like everyone else, endured a pandemic. There have also been bright spots, like the birth of our two beautiful children. But through it all, sitting down together at the table has kept us grounded. There’s no better day off for us than one spent hanging out at home as a family and cooking together, like we did when we first met. It’s different now, with the kids and more responsibilities, but the pleasure and joy of feeding each other still remain.

When we start the day, there’s usually toasted Rakkenji shokupan (naturally fermented milk bread) on the table. Our Sunday brunch is a Japanese breakfast, with miso soup and rice, delicate tamagoyaki (dashi rolled omelet) and a host of vegetable dishes, such as gomaae broccoli (broccoli with sesame sauce) and spinach ohitashi (spinach with soy sauce and bonito flakes). Lunch might involve onigiri (rice balls) and Japanese sandos (sandwiches), both perfect for eating on the go. Dinner may take the form of a simple noodle dish like yakisoba, roasted kabocha squash smothered in mirinsweetened ground pork, or a hotpot feast, a relaxed, interactive way to cook at the table. It’s not all strictly Japanese. There are pizza nights and pho and lots and lots of pasta. The next day, we usually repurpose the leftovers into bento boxes for our kids’ lunches.

We’ve seen Japanese food come a long way in this country—it’s no longer viewed as just sushi and teriyaki. But many Americans still regard it as the domain of chefs and experts, and we seek to change that. These are dishes you can definitely make yourself, as most of them are simple enough to cook for your family or friends on a weeknight. Japanese home cooking is comforting, humble, and achievable by anyone. The purchase of just a few pantry items can easily make it part of your standard repertoire. We’re not rigid about tradition, but the recipes are very much rooted in Japanese flavors, ingredients, and cooking techniques. Our book is a primer for home cooks who are eager to integrate Japanese flavors into their everyday meals. If you are already fluent in Japanese ingredients, we also use them in unexpected and delicious ways that may surprise you.

When we cook at the restaurant, we like to create something for people that they wouldn’t make at home. At home, we’re looking for the opposite—something that we can make over and over again, that is achievable, simple, and satisfying, and that we can potentially execute while holding an infant. As two working chefs, we used to have dinner around 9 or 9:30 p.m. Now we’re on the clock, and get food on the table by 6 or 7. Our son is seven years old and eats most everything, while our two-year-old daughter is hopefully following in his footsteps. By a certain time, we have to give them baths and put them to bed, and dinner has to fit into a certain parameter. More often than not, it’s about making rice, a protein, and then convincing our daughter to try a carrot. Our cooking has become a lot more practical, but it’s still important that pleasure has a place at the table.

As much as we look to Japan for inspiration, the cooking in our home is also influenced by what’s around us. Seasonal eating is central to both Japanese cuisine and ours. We pack up our kids and a week’s worth of compost and go shopping every Saturday, choosing produce from the great vendors that come to our neighborhood farmers’ market at McCarren Park in Brooklyn. Depending on where you are, you can find some of the best Japanese ingredients locally. Our favorite vegetables come from Bodhitree Farm, which grows an amazing array of Asian specialty produce.

Between spring and early winter, we get a majority of the vegetables we eat at home from them, whether it’s shishito peppers, nasu (eggplant), daikon radishes, or satsumaimo (Japanese sweet potatoes). Hauling back a refrigerator’s worth every week with two kids is a lot of work, but totally worth it.

In this book we wrestled, and wrestled some more, with the details of each recipe, recognizing that everyone’s home kitchen is a little different. We’ve included many cues, through sight, smell, touch, or taste, to guide you through them. Of course, cooking is an imperfect science, and requires you to use your senses, experience, and knowledge of your own equipment. Not everyone has the same set of pots; no two ovens or burners function identically. And we know how subjective taste can be. What is too much salt for some, is not enough for others. So when you are trying out these recipes, keep in mind what you like and the equipment you’re using, but most of all, trust your instincts. Nothing would make us happier than seeing you use our recipes as a jumping-off point—like Sawa did with her mother’s so many years ago—and eventually making them your own.

Copyright © 2023 by Sawako Okochi and Aaron Israel with Gabriella Gershenson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.