Introduction:

Why Do We Need to Demystify Disability? One billion. More than one billion people around the world are disabled. In fact, we’re the world’s largest minority. Statistically speaking, there’s a good chance this book is relevant to you. To narrow things down a little more, let’s do a quick gut check.

Have you ever tried to talk about disability and found yourself flustered over what words to use?

Have you ever shushed your kid for asking “what’s wrong” with a person who was using wheelchair?

Have you ever shared a news story about a disabled person on social media because you felt warm and fuzzy after reading it?

Have you ever compared yourself to someone with a disability to make yourself feel better about your own life?

If your response was “yes” to any of these, don’t stress. I’m not here to judge. Consider this book a safe space to learn and find answers to certain questions you might have but aren’t sure how to ask.

It’s pretty common for the mere mention of the word disability to evoke fear, confusion, and an endless stream of misconceptions. And often, people don’t realize their own biases. There’s much work yet to be done to change hearts and minds—or, at the very least, to get nondisabled people to stop treating disabled people as a weird cross between precious gems and alien creatures. And I am one of the many disabled people who are passionate about doing such work.

So, a little about me: I have multiple disabilities, including a physical disability, a hearing disability, and mental health disabilities. I use a wheelchair because I was born with Larsen syndrome (LS), a joint and muscle disorder that I inherited from my mom, Ellen, who also has it. You might think that our both having LS is a tragedy, but

we don’t. In my humble opinion, it’s pretty fantastic to have someone built into my life who just

gets me. But I know my mom didn’t always feel this way. When she and my dad, Marc, were considering having a baby, they sought out genetic counseling and were reassured that my mom wouldn’t pass on LS. Midway through the pregnancy, though, an ultrasound showed otherwise. My mom was absolutely overcome with guilt, fearing the worst for me and worrying that I’d resent her. And even though that couldn’t be further from the truth, I don’t blame her for these concerns. Society was even less disability-friendly while my mom was growing up than it is now. And once, when I was a baby, a woman was staring at us because she noticed our disabilities, and my mom overheard her say, “Look at what that mom did to her baby.” That rude comment left a sting that’s never gone away.

Even so, in the years since my birth, there’s been a continued shift toward greater acceptance and understanding of disability.

But all of us—nondisabled and disabled people alike—have more to learn about how to make the world a better, more accessible, more inclusive place. So how do we do this? There’s a philosophy I’ve come to embrace that informs everything I do:

If the disability community wants a world that’s accessible to us, then we must make ideas and experiences of disability accessible to the world.How can we expect understanding and acceptance of disability if we aren’t willing to share our insights and our stories? I recognize this isn’t always a popular line of thought among many disabled people. Educating others about the nuances of your daily life is a heck of a lot of work, and it can take an emotional toll—especially when there’s pushback, or the people who need to learn just won’t listen. It makes sense not to want to live our lives moving from one teachable moment to the next. We’d prefer to just live our lives, period.

However, the reality is that we’re not quite there yet. Whether I’m out and about in the world at large or just aimlessly scrolling through social media, I’m on high alert for ableism, stereotypes, stigma, and discrimination toward disabled people—and there is a lot of it to be found. So, for now, I believe that offering honest and sincere guidance and conversation remains a key part of the path forward for the disability community. That’s how progress has been made by the powerhouse disability activists who have come before me. It’s how we will continue forward. And if one person who reads this book thinks better of using disability as a slur or insult, or calls their representatives to advocate for a disability issue, or adds a ramp to the entrance of their shop, then we’re moving in the right direction.

There’s No Test at the EndThis book is a 101 on certain aspects of disability for anyone seeking to deepen their understanding and be a stronger ally, regardless of whether they identify as disabled. Use it as a reference, a resource, a jumping-off point, or a conversation starter. But remember, this isn’t a textbook or an exhaustive encyclopedia of disability. I’m not an academic, and I won’t be subjecting you to a pop quiz on what you’ve read. Instead, I hope that you’ll take what you learn from this book and apply it to real-world conversations and situations. And if you don’t get your language quite right on the first try, or you still have questions about whether a movie you saw recently represents disability in a positive light, that’s okay! I promise this isn’t a class that you’re going to fail.

The most important thing is that you aren’t just reading this book to try to get a gold star for doing the right thing or being nice to disabled people. Including, accepting, and supporting people with disabilities doesn’t make anyone a saint. That being said, learning about and understanding experiences outside of your own is a process, so don’t be too hard on yourself.

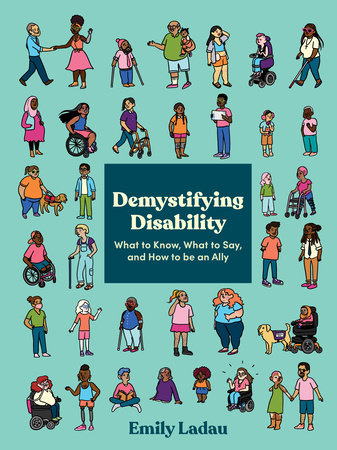

Disability Is Not One-Size-Fits-All At certain points, I’ll refer to the “disability community” as a collective term for disabled people. While we are indeed a diverse and beautiful community, it’s important to know that I’m not using this term to erase or gloss over our individual experiences.

There is no singular disability experience, and this book is in no way intended to be representative of every single person with a disability. We’re each our own person, and everyone’s thoughts and experiences are different. Because disability exists in infinite forms, even people who share the same diagnosis (if they have one) don’t have identical experiences.

My family is a perfect example of this. In addition to my having the same genetic disability as my mom, my Uncle Jonathan has it too. In some ways, our bodies are really similar. We’re all shorter than five feet, our thumbs are rounded like spatulas, our elbows are permanently bent, and we all have hearing loss. But we’re also each affected differently. My mom and I were both born with a cleft palate (an opening in the roof of the mouth), but my uncle wasn’t. Both my uncle and my mom can walk, but I can’t. Even with our shared DNA and shared disability, our experiences are unique.

So it’s important to remember that if you’ve met one disabled person, you’ve met one disabled person. And if you have a disability, then the only disability experience you’re an expert on is your own. The same logic is true in regard to this book. This is just one book on disability, and while my goal is to shine a spotlight on a wide-ranging spectrum of topics, perspectives, and experiences, please remember that I perceive the world through the lens of a person with an apparent physical disability. There’s a whole world of words and wisdom about disability out there. Wherever you are in your journey, whether this is the first thing about disability you’ve ever read or the hundredth, I encourage you to keep reading, keep learning, and keep going.

Copyright © 2021 by Emily Ladau. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.